Recovering Lost Legacies: Muslims and their Cultures of Learning

- Marwa Abdelghani

- Jun 5, 2015

- 3 min read

Islam is a religion that has been hijacked, several Muslim theologians proclaimed.

“Bringing back historical Islamic literature is crucial to understanding the roots of Islam that many have skewed and misinterpreted,” said Michael Cooperson, Professor of Arabic at UCLA.

Cooperson, along with professors Khaled Abou El Fadl, Chair of the Islamic Studies Department at UCLA, and Asma Sayeed, a professor of Islamic Studies at UCLA, examined the reasons why Islam has been proliferated into violence by a few individuals. The need for free and critical thinking in Islam, specifically in Islamic Studies departments at universities, was the point of conversation at a panel discussion Saturday afternoon at UCLA, hosted by the Muslim Reform Institute. Muslim Public Affairs Council President Salam Al-Marayati moderated the event titled, “Recovering Lost Legacies: Muslims and their Cultures of Learning.”

The Muslim Reform Institute [MRI], a think tank created to counter the extremist narrative of Islam, began two years ago and has partnered with institutions in providing a space for forums and discussions on how extremism impacts the Muslim family and Muslim community. Saturday’s discussion was just one of the many events that MRI plans to host.

Sixty people filled room 314 of Royce Hall, eager to hear the different scholars’ work in the Islamic Studies program at UCLA.

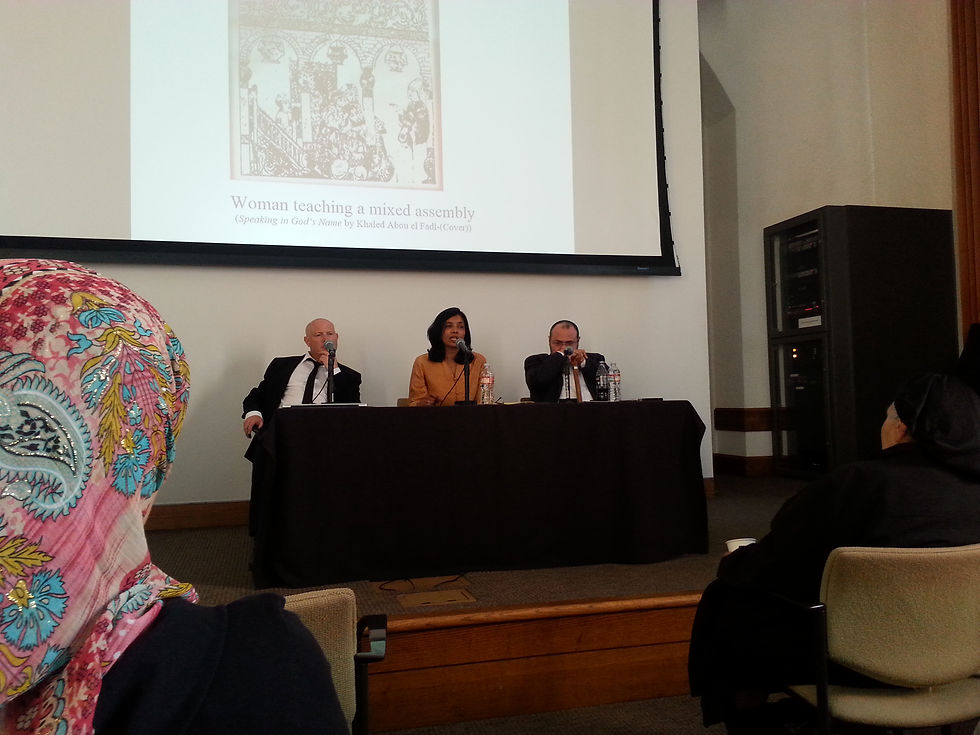

Photograph by Marwa Abdelghani

Cooperson spoke about his work in translating historical religious books from Arabic to English. He spent years translating the biography of a scholar named, Imam Ahmed Ibn Hanbal, written by Ibn Al-Jawzi. Cooperson humorously showed the audience his step by step methodology of translating Arabic scripture to everyday English.

Asma Sayeed, who has done extensive work in bringing back the legacies of female scholars, presented her findings about Zainab Bint Al-Kamal, a transmitter of the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad, whom Muslims regard as the last prophet who delivered the message of God. Bint Al-Kamal lived in the 8th century in what is now Damascus, Syria.

Part of the work that the Islamic Studies department of UCLA hopes to do is bring back the lost aspect of the major role women played as scholars of Islam. Sayeed described how the front cover of Abou El Fadl’s book titled, Speaking in God’s Name, has a woman teaching a mixed assembly.

“By age 75,” Sayeed said, “Al-Kamal had over 100 students.”

A question from the audience challenged the panelists to think hard about how far their work has gone: “How far are we in spreading Islamic knowledge?” Abou El Fadl stole the mic to eagerly respond: “We are still in our infancy.” He described how knowledge is based on data and collections of analyses and methodologies, which we lack. “We do not yet have the institutional formulas necessary to create fruitful and ethical receptions of our research,” he said.

Abou El Fadl brought up a critical point about what Islamic discourse should potentially embody, which Saturday afternoon was a perfect example of: “Discourse is inclusive. It speaks to Muslims, but is also subject to critical evaluation by Muslims and non-Muslims.”

Cooperson reiterated this point in his presentation. He described the Arabic term, “adab,” which traditionally means literature and teachings, but can also mean morals and ethics. Part of having an ethical conversation about religion and Islam is by being inclusive.

Ahmed Younis, an audience member and a professor at Chapman University, asked the panelists: “How do we allow young people who are not deeply educated on Islam and its history to escape the parochial?”

In order to escape from the parochial studies of Islam, we must have better standards of knowledge and research, emphasized Abou El Fadl.

MRI and the UCLA Islamic Studies Department are eager to continue expanding their resources and partnerships in order to “escape” the parochial, and focus on how Islam is relevant to today’s society.

Comments